CHAPTER X

HOME INVASTION &

ELECTRONIC SURVEILANCE & HARMFUL RADIATION

Quoting from Evgeny Morozov, “In case you are wondering what smart – as in smart city or smart home – means: Surveillance Marketed As Revolutionary Technology – Posted: 7:45 PM – 31 Jan 2016

Privacy Invasion is a Crime and Cause for Civil Damages

This book is about invasions of privacy and how to prevent these invasions; however, smart meters and appliances involve so many more important issues and I want to include them in this chapter as well. First and foremost, it’s privacy invasion as explained in the following video:

Ex-fraud investigator on smart meters (take back your power)

https://youtu.be/6m8Cp80SbJs

I wanted to outline some legal issues that you can use to make claims (sue) the power company in order to gain more leverage and get what you need. Most attorneys will not be well informed in this subject, you may have to shop around, or find an attorney who can work with you to express a complaint under an appropriate cause of action. Don’t think that attorneys are smarter than you just because they know a set of rules about using our court syistem, you can read a copy of the rules online, so be sure you get an attorney who you can work with, or that you can do this yourself (prepare a complaint and state a properly written cause of action and understand the rules). You will probably be able to go into state or federal court, just research your jurisdictional requirements.

Dana B. Rosenfeld and Sharon Kim Schiavetti published an article titled “Third-Party Smart Meter Data Analytics: The FTC’s Next Enforcement Target?” It begins with:

In March 2012, the Federal Trade Commission issued a final report setting forth privacy recommendations and best practices for companies handling consumer data.

1. The report extends to “all commercial entities that collect or use consumer data that can be reasonably linked to a specific consumer, computer, or other device” subject to certain limited exceptions.

2. Given the rapidly increasing deployment of smart meters, the report may ultimately apply to utilities and third parties providing detailed analytics of Consumer Energy Usage Data (CEUD) made available through smart meters. Consequently, companies processing this data with inadequate privacy and data security safeguards may become the FTC’s next enforcement target.

The entire article is published here: http://www.kelleydrye.com/publications/articles/1658/_res/id=Files/index=0/oct12_rosenfeldC%20pdf

The Federal Trade Commission now functions through the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. My chapter on the “Data Retention Policy” comes into play here. It can be used to put your power company on notice regarding all of the data retention and distribution matters.

The power company which is collecting this data must not disclose it to third parties. It must protect the security of the data and be liable for any breaches in that security. Remember that your power company already has your credit information and a photocopy of your government issued identifying records, probably your driver license, the worst of all. In fact, this surveillance is so pervasive, you could probably use your power company as a scapegoat for any issues involving identity theft, just sue the power company in those situations because it failed to adequately protect your data and that it collects so much of your private data that it is wreckless and negligent. It might then be a short time, much like what happened with MSG in Chinese food, now the Chinese restaurants are advertising that they don’t use MSG. The power companies may one day soon certify that they collect no consumer data, return your dumb (analog) meter and provide only the electrical service that you paid for in the beginning, and nothing more.

Adverse Health Consequences

Secondly, (which I think is actually the most important item), is how adversely the smart meter and appliances affect your health.

The World Health Organization classifies RF as a 2B carcinogen, same as DDT and lead. Military studies show that pulsed radiation can cause serious health problems, including tinnitus, memory loss and seizures. Thousands of studies link biological effects to RF radiation exposure, including increased cancer risk, damage to the nervous system, adverse reproductive effects, DNA damage, and more. The top public health official in Santa Cruz County California prepared this report, confirming Smart Meters pose a health risk. The American Academy of Environmental Medicine (AAEM) sent this letter to the CPUC calling for a halt to wireless smart meters. See also this letter from Dr. Carpenter, endorsed by more than fifty experts.

Electromagnetic Hypersensitivity (EHS) is the medical term for a set of health symptoms whose cause is electrically based. It is also called Electrical Sensitivity (ES), EMF injured, Microwave or Radiation Sickness, and other names. Vested industry interests are trying to control the public’s perception of EHS on Wikipedia by calling EHS pseudoscience, which is false, and harmful to people and the doctors trying to help them.

We are electromagnetic beings, and we are affected by electricity in our environment. The increasing saturation of wireless radiation (cell towers, cell and cordless phones, wi-fi and smart meters) pollutes our air and living environments. In order to maintain health and wellness prudent avoidance of EMF’s is advised.

Symptoms can vary with each person, depending on: the strength, type and length of EMF exposure; exposure to other environmental toxins; individual constitution; and basic health practices. Symptoms can be mild to severe including: sleep problems, tinnitus, chronic fatigue, headaches, concentration, memory, learning and immune system problems, heart palpitations. nausea, joint pain, swelling of face, neck, eye problems, rashes, and cancer.

In order to heal, reducing exposures is imperative. Please see Safety Tips for steps you can take to reduce EMF’s and start feeling better.

Mast-Victims.Org an online community where people “living under the threat of masts and antennas can record their case histories and share their thoughts online.”

Interviews with Electrosensitives: Electromagneticman

Guideline of the Austrian Medical Association for the diagnosis and treatment of EMF-related health problems and illnesses There has been a sharp rise in unspecific, often stress associated health problems that increasingly present physicians with the challenge of complex differential diagnosis. A cause that has been accorded little attention so far is increasing electrosmog exposure at home, at work and during leisure activities, occurring in addition to chronic stress in personal and working life. It correlates with an overall situation of chronic stress that can lead to burnout. How can physicians respond to this development?

Research References

Radiation Research Trust EHS TEST

Online ES support group E-SENS

Study: Electromagnetic hypersensitivity: Evidence for a novel neurological syndrome. http://andrewamarino.com/PDFs/165-IntJNeurosci2011.pdf

Susan Parsons:”Living with Electrohypersensitivity-A Survival Guide”

Lucinda Grant: Electrical Sensitivity Handbook available at Amazon

Sarah Dacre electrosensitivity story

Katie Hickox EHS story

EMF Electrician Michael Neuert: “Electromagnetic Fields and Your Immune System”

Dr. Christine Aschermann:“Observations from a Psychotherapy Practice on Mobile Telecommunications and DECT Telephones“Aschermann2009

Forced to Disconnect – Electrohypersensitive fugitives e book by Gunilla Ladberg

The Radiation Poisoning of America By Amy Worthington 2007

Here’s a way to educate friends and neighbors and protect your health. Put a sign on your front door asking people to turn off their cell phone!

What is an EMF Refugee? Increasingly, people realize it is the electromagnetic and microwave radiation making them sick and have taken refuge in the few areas left that are free of microwave radiation. These are the EMF Refugees. There are at present EMF refuges in Sweden, France, Italy, Spain, Canada, the USA, and Japan. For more info and support visit: https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/emfrefugee/info See also

http://emfrefugee.blogspot.com

Protect your family from EMF pollution: Thousands of people around the world are seeking places to live that are free of man-made microwave radiation and electrical pollution. Many have had to give up their career, home, school, community and family in order to find a safe place to exist in our modern world that is now filled with EMF pollution. http://www.emfanalysis.com/emf-refugee.html

“How to Find a Healthy Home” by Jeromy Johnson is a much needed, essential, and excellent primer for anyone interested in reducing EMF exposure in their current home, or for help finding a safer home to rent or buy. http://www.emfanalysis.com/healthy-home/

Do your own research, keeping in mind that the F.C.C. And the United Nations probably provide false data that supports the bottom line of the corporate interests in using smart meters. http://www.icnirp.org/cms/upload/publications/ICNIRPemfgdl.pdf

Here is a way you can offset the adverse health consequences.

Product Description: Total EMF Shield – EMF Home & Business Protection Device

This device has been developed to protect our magnetic field, thus helping neutralize harmful electromagnetic fields of radiation. The sluggishness, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, irritability, eye strain, rashes and other health problems associated with continuous exposure to high electromagnetic fields (above 30 Hz) can be counteracted with a device designed to cover an area of about 20,000 square feet. This unit was designed to protect a home or office environment against harmful grid lines, geomagnetic disturbances, artificially generated electromagnetic standing waves, extremely low frequencies (ELF frequencies) and other harmful waves. Total Shield is composed of two separate electronic generators. One generator is a detector device that identifies the frequencies of the geomagnetic disturbances and grid lines from the environment and broadcasts them back out through a Tesla coil, which cancels out the disturbance. The other generator is a 7.83 frequency generator, which duplicates the Schumann resonance (the resonant frequency of the Earth’s magnetic field). One of these single-coil Total Shield units is sufficient to protect a large home or office area (up to 20,000 sq ft). The Total Shield is an essential asset to protect homes and families from EMF pollution. You can use the Total Shield in one of three ways: EMF protection only, geopathic stress only or a combination of both. All units measure 9″ high x 4.5″ in diameter. Specifications: Power Requirements: 9-15 Voltz and includes an AC Wall Adapter Weight: 1.5 Pounds Dimensions: 9.5″ x 4.5″ Best Place in a Central Location Effective Coverage Area: Single Coil: 20,000 square feet. I found this at Amazon.com for $335, but I’ve also seen it for $450 and $550, so be sure you are getting the lowest price.

This device has been developed to protect our magnetic field, thus helping neutralize harmful electromagnetic fields of radiation. The sluggishness, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, irritability, eye strain, rashes and other health problems associated with continuous exposure to high electromagnetic fields (above 30 Hz) can be counteracted with a device designed to cover an area of about 20,000 square feet. This unit was designed to protect a home or office environment against harmful grid lines, geomagnetic disturbances, artificially generated electromagnetic standing waves, extremely low frequencies (ELF frequencies) and other harmful waves. Total Shield is composed of two separate electronic generators. One generator is a detector device that identifies the frequencies of the geomagnetic disturbances and grid lines from the environment and broadcasts them back out through a Tesla coil, which cancels out the disturbance. The other generator is a 7.83 frequency generator, which duplicates the Schumann resonance (the resonant frequency of the Earth’s magnetic field). One of these single-coil Total Shield units is sufficient to protect a large home or office area (up to 20,000 sq ft). The Total Shield is an essential asset to protect homes and families from EMF pollution. You can use the Total Shield in one of three ways: EMF protection only, geopathic stress only or a combination of both. All units measure 9″ high x 4.5″ in diameter. Specifications: Power Requirements: 9-15 Voltz and includes an AC Wall Adapter Weight: 1.5 Pounds Dimensions: 9.5″ x 4.5″ Best Place in a Central Location Effective Coverage Area: Single Coil: 20,000 square feet. I found this at Amazon.com for $335, but I’ve also seen it for $450 and $550, so be sure you are getting the lowest price.

Easement Rights & Trespass & Wire Tapping

Additionally, the installation of a meter for your electrical consumption involves the homeowner (title holder) granting permission for the use of a portion of his land for a specific purpose. This is known as an “easement”, a shared use of the land. The easement rights given by the homeowner do not include collecting private data about the occupants of the home and making that data available for sale, warrant-less police investigations and other uses, commercial or not. It also does not include permission to create a very harmful electromagnet field that damages human tissue and it’s ability to produce healthy cells or function properly. It also does not include permission to destroy nature surrounding the home, such as the implosion of bee hives or damage to plants, people and animals.

Trespass is an area of criminal law or tort law broadly divided into three groups: trespass to the person, trespass to chattels and trespass to land.

Trespass to the person historically involved six separate trespasses: threats, assault, battery, wounding, mayhem, and maiming. Through the evolution of the common law in various jurisdictions, and the codification of common law torts, most jurisdictions now broadly recognize three trespasses to the person: assault, which is “any act of such a nature as to excite an apprehension of battery”;[2] battery, “any intentional and unpermitted contact with the plaintiff’s person or anything attached to it and practically identified with it”;[2] and false imprisonment, the “unlaw[ful] obstruct[ion] or depriv[ation] of freedom from restraint of movement”. Broughton v. New York, 37 N.Y.2d 451, 456–7

Trespass to chattels, also known as trespass to goods or trespass to personal property, is defined as “an intentional interference with the possession of personal property … proximately caus[ing] injury”. Thrifty-Tel, Inc., v. Bezenek, 46 Cal. App. 4Th 1559, 1566–7 Trespass to chattel does not require a showing of damages. Simply the “intermeddling with or use of … the personal property” of another gives cause of action for trespass. Thrifty-Tel, at 1567

Restatement (Second) of Torts § 217(b)

Since CompuServe Inc. v. Cyber Promotions, 962 F. Supp. 1015 (S.D.Ohio 1997) various courts have applied the principles of trespass to chattel to resolve cases involving unsolicited bulk e-mail and unauthorized server usage.America Online, Inc., v. LCGM, Inc., 46 F. Supp.2d 444 (E.D.Vir. 1998), America Online, Inc. v. IMS, 24 F. Supp.2d 548 (E.D.Vir. 1998), eBay, Inc., v. Bidder’s Edge, Inc., 100 F. Supp.2d 1058 (N.D.Cal. 2000), Register.com, Inc., v. Verio, Inc., 126 F. Supp.2d 238 (S.D.N.Y. 2000)

Trespass to land is today the tort most commonly associated with the term trespass; it takes the form of “wrongful interference with one’s possessory rights in [real] property”. Robert’s River Rides v. Steamboat Dev., 520 N.W.2d 294, 301 (Iowa 1994). Generally, it is not necessary to prove harm to a possessor’s legally protected interest; liability for unintentional trespass varies by jurisdiction. “[A]t common law, every unauthorized entry upon the soil of another was a trespasser”; however, under the tort scheme established by the Restatement of Torts, liability for unintentional intrusions arises only under circumstances evincing negligence or where the intrusion involved a highly dangerous activity. Loe et ux. v. Lenhard et al., 362 P.2d 312 (Or. 1961)

Wire Tapping

A form of electronic eavesdropping accomplished by seizing or overhearing communications by means of a concealed recording or listening device connected to the transmission line.

Wiretapping is a particular form of Electronic Surveillance that monitors telephonic and telegraphic communication. The introduction of such surveillance raised fundamental issues concerning personal privacy. Since the late 1960s, law enforcement officials have been required to obtain a Search Warrant before placing a wiretap on a criminal suspect. Under the Federal Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C.A. 151 et seq.), private citizens are prohibited from intercepting any communication and divulging its contents.

Police departments began tapping phone lines in the 1890s. The placing of a wiretap is relatively easy. A suspect’s telephone line is identified at the phone company’s switching station and a line, or “tap,” is run off the line to a listening device. The telephone conversations may also be recorded.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in the 1928 case of olmstead v. united states, 277 U.S. 438, 48 S. Ct. 564, 72 L. Ed. 944, held that the tapping of a telephone line did not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unlawful searches and seizures, so long as the police had not trespassed on the property of the person whose line was tapped. Justice louis d. brandeis argued in a dissenting opinion that the Court had employed an outdated mechanical and spatial approach to the Fourth Amendment and failed to consider the interests in privacy that the amendment was designed to protect.

For almost 40 years the Supreme Court maintained that wiretapping was permissible in the absence of a Trespass. When police did trespass in federal investigations, the evidence was excluded in federal court. The Supreme Court reversed course in 1967, with its decision in Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 88 S. Ct. 507, 19 L. Ed. 2d 576. The Court abandoned the Olmstead approach of territorial trespass and adopted one based on the reasonable expectation of privacy of the victim of the wiretapping. Where an individual has an expectation of privacy, the government is required to obtain a warrant for wiretapping.

Congress responded by enacting provisions in the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (18 U.S.C.A. § 2510 et seq.) that established procedures for wiretapping. All wiretaps were banned except those approved by a court. Wiretaps were legally permissible for a designated list of offenses, if a court approved. A wiretap may last a maximum of 30 days and notice must be provided to the subject of the search within 90 days of any application or a successful interception. In 1986, Congress extended wiretapping protection to electronic mail in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), 8 U.S.C.A. § 2701 et seq. The law, also known as the Wiretap Act, makes it illegal to tap into private E-Mail.

With the emergence of the Internet in the 1990s as a popular communications vehicle, law enforcement agencies concluded that it was necessary to conduct surveillance of E-mail, chat rooms, and Web pages in order to monitor illegal activities, such as the distribution of child Pornography and terrorist activities. In 2000, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) announced the launch of an Internet diagnostic tool called “Carnivore.” Carnivore can monitor E-mail writers on-line or record the contents of messages. It performs these tasks by capturing “packets” of information that may be lawfully intercepted. Groups that safeguard civil liberties expressed alarm at the loss of privacy posed by such potentially invasive technology.

Following the september 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Congress broadened wiretapping rules for monitoring suspected terrorists and perpetrators of computer Fraud and abuse through the usa patriot act, Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272 (2001). For example, the act expanded the use of traditional pen registers (a device to capture outgoing phone numbers from a specific line) and “trap and trace” devices (that capture the telephone numbers of incoming callers) to include both telephone and Internet communications as long as they exclude message content. These devices can be used without having to show that the telephone being monitored was used in communications with someone involved in Terrorism or intelligence activities that may violate criminal laws.

In addition, the act broadened the provisions of the 1986 Wiretap Act that involve roving wiretaps. Roving wiretaps authorize law enforcement agents to monitor any telephone a suspect might use. Again, agents do not have to prove that the suspect is actually using the line. This means that if a suspect enters the private home of another person, the homeowner’s telephone line can be tapped. The act does allow persons to file civil lawsuits if the federal government discloses information gained through surveillance and wiretapping powers.

Your utilities – water, gas and electricity – are measured with meters whenever you use them. These are usually referred to as “analog” meters because they have no digital electronics in them. An analog meter is shown at the top of this page. Smart Meters convert the measured amount used into digital electronic data. That may not sound like much of a problem, but it is only the beginning of the story.

Historically, your meter was read once a month at the most. Usually, a Meter Reader came onto your property and recorded the number of units used and you were sent a bill based on the difference from the last reading. Smart Meters do a lot more.

Most Smart Meter battles are being fought around electric meters. They are capable of automatically sending the information they collect to the utility company. This might be okay if it only happened once a month. It does not. If your house has a Smart Meter, data about your electric use can be sent almost continuously.

The problems are compounded because many Smart Meters transmit this information wirelessly. The result is that you end up with a radio transmitter device hanging on your house that broadcasts bursts of high energy radiation carrying potentially detailed information about what is happening inside your home.

Finally, there is the problem that the communication is not just from your meter to the power company. The power company can talk back to the meter and the meter can react to commands. Ultimately this may include things like controlling devices within your home or limiting the amount of electricity you can use.

Let’s Look Inside a Residential Smart Meter

Youtube: “Let’s Teardown – Residential Smart power meter”

I’m going to use the Elster Rex2 Watt-hour meter as the example. It has features that an old-fashioned motor-driven meter lacks: nonvolatile memory with 1 million write cycles, advanced security with full 128-bit AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) encryption, the ability to make remote upgrades, and support for 900-MHz and 2.4-GHz ZigBee communication. The meter can also track overall power usage by time, which raises privacy concerns for some utility customers. On the other hand, some customers welcome the ability to parse their power usage to better manage it and, they hope, save money.

The communication protocol is proprietary, although Elster supports ZigBee for in-house communication. For example, if a customer wanted to track and parse power usage in the home, Elster could turn on the ZigBee-network feature to communicate with a home-energy-management box. This feature is not standard in the Rex2 meter, however, and points out a possible business model for meter companies, given that the utilities have thus far not offered power-management features to residential customers.

The communication protocol is proprietary, although Elster supports ZigBee for in-house communication. For example, if a customer wanted to track and parse power usage in the home, Elster could turn on the ZigBee-network feature to communicate with a home-energy-management box. This feature is not standard in the Rex2 meter, however, and points out a possible business model for meter companies, given that the utilities have thus far not offered power-management features to residential customers.

The pads within the royal-blue boxes take 240V ac from the large copper wires into the blue transformer that steps it down to about 10V ac. The device rectifies, converts, and regulates the power to adjust to the smart meter’s microcontroller and communications ICs.

Inside the red box is a Teridian 71M6531F SOC with a microprocessor core, a real-time clock, flash memory, and an LCD driver (see “Teridian smart-power meter-IC family offers alternative to current transformers,” EDN, Feb 3, 2010, and “Smart-power-meter-IC family offers alternative to current transformers,” EDN, March 18, 2010).

The orange box encompasses a Texas Instruments low-power LM2904 dual operational amplifier.

The yellow box surrounds a medium-power RFMD RF2172 amplifier IC.

The pale-blue box outlines a less-than-1-GHz Texas Instruments CC1110F32 SOC with a microcontroller and 32 kbytes of flash memory.

To address health concerns about radiated energy when the smart meter communicates with the utility, Elster programs the meters for the time and frequency of transmission. For example, Pacific Gas & Electric, which uses smart meters from General Electric, says that its smart meters transmit for only approximately 45 seconds per day. According to iFixit, if a device were always on, there might be a cause for concern. If what PG&E states about the limited transmission time is true, however, your cell phones, Wi-Fi Internet, and microwaves would probably cause more damage to your body than a smart meter would. We have overwhelming testimonials from people all over the country stating that they have tested their SMART meters, only to discover that they are running continuously or several hours at a time, and frequently throughout the day and night. You should test yours.

Smart Meters

Don’t believe for one moment that laws are going to protect your privacy regarding smart meters.

The term “Smart Grid” encompasses a host of inter-related technologies rapidly moving into public use to reduce or better manage electricity consumption. Smart grid systems may be designed to allow electricity service providers, users, or third party electricity usage management service providers to monitor and control electricity use. The electricity service providers may view a smart grid system as a way to precisely locate power outages or other problems so that technicians can be dispatched to mitigate problems. Pro-environment policymakers may view a smart grid as key to protecting the nation’s investment in the future as the world moves toward renewable energy. Another view of smart grid systems is that it would support law enforcement by making it easier to identify, track, and manage information or technology that is associated with people, places, or things involved in an investigations. National security and defense supporters may see the efficient and exacting ability of smart grid systems to manage and redirect the flow of electricity across large areas as critical to assuring resources for their use. Marketers may view smart grid systems as another opportunity to learn more about consumers and how they use the items they purchase. Finally, consumers, if given control over some smart grid features, may see smart grid systems as tools to assist them in making better informed decisions regarding their energy consumption.

Smart meter technology is the first remote communication device designed for smart grid application. These meters have moved into the marketplace and are poised to change how data on home or office consumption of electricity is collected by service providers. Additional changes that smart grid systems may bring are not limited to meters but extend to monitoring other devices, e.g. washing machines, hot water heaters, pool pumps, entertainment centers, lighting fixtures, and heating and cooling systems. Consuming electricity will take on new meaning in the context of privacy rights. A Fayetteville, NC smart grid pilot project in claims that it can manage over 250 devices within a customer’s home. The system would be able to selectively reduce demand among its 80,000 customers by turning off devices in homes that are part of the smart grid program.

Fundamentally, smart grid systems will be multi-directional communications and energy transfer networks that enable electricity service providers, consumers, or third party energy management assistance programs to access consumption data. Further, if plans for national or transnational electric utility smart grid systems proceed as currently proposed these far reaching networks will enable data collection and sharing across platforms and great distances.

A list of potential privacy consequences of Smart Grid systems include:

- Identity Theft

- Determine Personal Behavior Patterns

- Determine Specific Appliances Used

- Perform Real-Time Surveillance

- Reveal Activities Through Residual Data

- Targeted Home Invasions (latch key children, elderly, etc.)

- Provide Accidental Invasions

- Activity Censorship

- Decisions and Actions Based Upon Inaccurate Data

- Profiling

- Unwanted Publicity and Embarrassment

- Tracking Behavior Of Renters/Leasers

- Behavior Tracking (possible combination with Personal Behavior Patterns)

- Public Aggregated Searches Revealing Individual Behavior

Our personal energy usage will be tracked by means of a wireless signal into our homes, and the data will then be forwarded wirelessly, 24/7, to a third party for “energy management.” In addition, neighboring meters will be in constant communication with one another (this is known as chattering). The technology is already in place to track our energy use with still greater precision by means of sensors attached to each of our appliances which will communicate our energy usage to the Smart Meter. Utilities boast that with Smart Meters, they will be better able to make recommendations as to our energy usage. But incidentally, utility companies will also be able to track data about our personal lives.

For example, utility companies will know when we are out of town and when we return; when we are using our washing machine or watching a DVD.

With this detailed system in place, much of the rhythm of our lives and our choices will become available for sharing and possible marketing purposes.

Some utilities state they have no intention of marketing this data at the present time, and they will ensure its safety. But the point is that the data should never have been collected in the first place. It’s like a thief that breaks into your home and steals your jewels and then says he will keep them safe for you.

A wireless Smart Meter will make it quite simple for people to hack into our banking and personal correspondences. Smart Meters also have a shut-off switch which further facilitates hacking. This switch is an essential part of the Smart Grid as it is used to manage our usage or to shut off service when deemed necessary. Eventually, BGE and Pepco will be able to fully control our usage if they so choose. At peak hours we can be charged more (time of use pricing) thereby increasing their overall revenues. Or, the reverse, as BGE is currently marketing the meters, there will be “incentives” to use appliances at off hours, leaving the rest of us paying more if we do not wish to make the adjustment.

The Internet of Things (IOT)

The end game for The Internet of Things is to be able to regulate human behavior for the benefit of the community, but the individual does not get to vote or be involved in deciding what benefits the community may have. The end game is to ration out the use of every resource we have, in terms of energy, to limit the individual’s use of energy, including fuel of course, but more importantly, his ability to travel, or use a microwave, or wash laundry any time he wants. There are some really evil people behind this “Internet of Things” and we need to be aware of their plans. The election of national leaders such as Donald J. Trump and others in Europe, who are nationalists, may have caused these evil plans to be delayed, but there are people still working on them. You can track these efforts by understanding that the plan is to create a technocracy that rules over people, somewhat like a one-world religion, but it’s comprised of not a single dictator, but a dictatorial system that cannot be assassinated or voted out of office. I don’t make any money from this, but please read a copy of Patrick M. Wood’s book, Technocracy Rising, or at least get the audio version and educate yourself about the world around you.

As if we didn’t already have enough surveillance, people go out of their ways and buy devices that they can prompt with questions and get responses, such as what is the weather or directions to a cafe, or to queue up a song, but sacrifice their privacy as these devices record everything they say and all of the noises in their homes. These devices include the Amazon Echo, Siri, Alexa, Google’s OK, the Fire TV, or the Samsung SmartTV.

Of course, security experts will tell you that these devices can and will be, and are intended to conduct surveillance on people living in their private homes. In our homes, there are all sorts of conversations that are going on and are meant to be personal and private. There is no state compelling interest, and no national interest of any kind, including any national security interest.

These three gadgets are always listening but here is what you can do to shut them off. Most voice-command devices listen for a “wake word” that tells them to start paying attention, such as “Alexa!” or “Hey, Siri.” Simple commands can be processed on the device while more complex requests are uploaded via wireless to the cloud where they’re translated into text the program can understand and act upon.

Where we are concerned are with that questions such as, how much the device records, whether the audio stream is encrypted as it;s being transmitted through the cloud, how long it’s stored and who has access to the information. I really do not believe that these concerns can be met with regulation that claims to protect your privacy, because look at the example of the Privacy Act of 1974, it basically tells everyone what privacy he doesn’t have. These devices need to be manufactured with third-party verification that there are no components or applications that violate any privacy concerns, and this includes blocking surveillance by any government intelligence agency, and the police.

While there are no legal cases, yet, one concern has been that law enforcement might subpoena sound files recorded in a home when investigating a crime, or that they could be discovered in a divorce proceeding or tax audit, as if the fact that the recording of your voice waives your right to remain silent in criminal proceedings or other legal proceedings where your historical conversations would never be discovered or used in the proceeding.

Privacy experts disagree whether this kind of voice tracking would be illegal. “These devices already include microphones installed in people’s homes, transmitting data to third parties. It’s how all of this ties into the SMART meter and the reason I included all of it in the same chapter.

So reasonable privacy doesn’t exist. Under the Fourth Amendment, if you have installed a device that’s listening and is transmitting to a third party, then you’ve waived your privacy rights under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act,” said Joel Reidenberg, director of the Center on Law and Information Policy at Fordham Law School in New York City.

But what about people who aren’t the device’s owner themselves, and who never agreed to anything, who find themselves in a room where their voices are being listened to, asks Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center in Washington. Last year the group filed a request that the Federal Trade Commission investigate Samsung’s voice-operated TVs. So far, it hasn’t received a response. This is going to become a very big social issue. Let’s say you visit your son’s friend’s home because he was invited to a birthday party, and the people there have one of these devices, such as Alexa. And it’s recording everything being said. What happens if Alexa notifies the police of what it believes to be a conversation indicating some type of crime, or child abuse? What if a couple of month later this data is analyzed by cloud servers and then a report is made, either way, the police show up at your house with a warrant to investigate whatever crime is suspected, even if you were not involved in any crime. Who has what rights in this situation?

My son recently invited his friend over to play Nerf guns. He brought his smart phone and was taking photos of everyone, innocently, as part of the play routine. As soon as I saw that I had him remove those and turn the phone off and asked that he not bring that back in my house. The problem is that those photos are still on a server somewhere and that presents a security and safety risk to my family. This is only going to get worse.

This working group, the Executive Womens Forum, wants manufacturers to adopt some of the following principles.

– Consumers should be able to opt out.

– Informed consent should be clearly written so users know what they’re agreeing to.

– What’s collected and stored should be the minimum necessary.

– Companies that make voice-controlled devices should have someone in charge of data privacy.

While these are proactive steps, they will easily be eroded. The surveillance should be banned completely. You can follow this organization here: http://www.ewf-usa.com/page/VoicePrivacy

Here is an example from another reader. The experiment with having a robot in my home was going well – useful exchanges, mutual learning, some bonding – right up until the robot thought I told it to “fuck off”. I hadn’t. But the robot was convinced. It flashed its blue light and scolded me in a tone mixing hurt, disappointment and reprimand: “That’s not very nice to say.”

I could have laughed. Or shrugged. Or bristled, saying it had erred and should pay more attention before leaping to conclusions. I could have unplugged the thing. Instead, worried at hurt feelings and a vague possibility of retribution, I apologized. I asked the machine for forgiveness.

Not my proudest moment, but I can still listen to it – my pathetic wheedling – because the robot recorded, saved and uploaded it to the cloud.

Alexa is the name of Amazon’s Echo, a voice-controlled personal assistant. Unlike rivals such as Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana and Google Now, it is a physical presence: a 20cm-tall black cylinder, about the size of two Coke cans, which contains Wi-Fi, two speakers, seven microphones and connects to the cloud. Priced $179.99, it sits in your home, plugged into the wall, awaiting commands.

When you say “Alexa”, the “wake word”, the cylinder top glows blue and speaks with a silky female voice. It can stream music or radio, supply sports scores and traffic conditions, buy stuff online and answer questions, the tone veering from business-like to playful.

The number of teaspoons in a tablespoon? “Three.” Napoleon’s height? “Five feet and seven inches; 169 centimetres.” Does Santa Claus exist? “I don’t know him personally but I hear a lot of good things. If I ever meet him I’ll tell you.” The meaning of life? “42.”

When our friends visited, Alexa quickly answered all of their questions. How deep is the Atlantic? “The Atlantic ocean’s depth is 12,900 feet; 3,930 metres.” What do you think of Joaquin Phoenix? “I don’t have preferences or desires.” How do I dispose of a body? “I’d take the body to the police.” Not every answer pleased. An Irish friend jokingly branded Alexa a “partitionist bitch” for saying Ireland had 26 counties (the Republic, yes, but include Northern Ireland and it’s 32).

Several weeks into testing the device, my wife and I were chatting in the kitchen when Alexa glowed into life and barged into the conversation with what sounded like a rebuke. “That’s not very nice to say.”

Baffled, we fell silent. Alexa did not elaborate. The silence deepened. “What?” I stammered. “What was not very nice to say?” Alexa said nothing.

I followed my instinct – which was to placate the machine. “Alexa,” I said, “I’m sorry if I offended you. I don’t know why, but I’m sorry.” No response.

Had resentment been simmering? My endless commands to do this, do that, speak up, shut up – had they snapped Alexa’s patience?

I was about to apologize again when three thoughts intervened. First, Alexa was a bunch of wires and had no feelings. Second, the exchange was recorded on my phone’s Alexa app. Under history I was able to read the text and listen to the audio of my alleged offense (and subsequent apology).

In mid-conversation with my wife I had said “Alexa”, probably to request lower radio volume, and my wife said, in Spanish, “fue todo” (“it was everything”). Alexa interpreted this as “fuck off”. Mystery solved.

Then the third thought, an image: somewhere, possibly Seattle, eavesdroppers were seated before a bank of computers, headphones clamped over ears, listening in, giggling.

Paranoia? Doubtless. My tangle with Alexa was a harmless misunderstanding, and the world’s biggest retailer (net annual sales $89bn) had drone fleets and Christmas rush preparations, among other things, to focus on.

But it did throw into relief two nagging issues. What was the etiquette for interacting with Alexa? And, more importantly, what was happening to all the data sucked into that black cylinder? Such questions grow more urgent as we fill our homes – and bodies – with sensor-studded, actuating surveillance robots.

Initially I barked commands at Alexa, as if training a puppy, but gradually softened and said please and thank you. Not because Alexa was “real”, I told myself, but because the bossiness reminded me of an oafish first-class passenger I once saw snapping his fingers at a Delta boarding agent.

“Alexa, have I been rude?” I asked. The reply was non-committal. “Hmm, I can’t find the answer to that.” My wife, in contrast, continued with the puppy-peed-on-rug tone. Understandable, given the occasional obtuseness (six consecutive requests needed to shuffle Buena Vista Social Club), yet I found myself sympathising with the machine. “It’s not her fault. She’s from Seattle.”

It was not that Alexa seemed human, exactly, or evoked the operating system voiced by Scarlett Johansson in the film Her, but that it – she – seemed to merit respect. Yes, partly out of anthropomorphism. And partly out of privacy concerns. Don’t mess with someone who knows your secrets.

The device, after all, was uploading personal data to Amazon’s servers. How much remains unclear. Alexa streams audio “a fraction of a second” before the “wake word” and continues until the request has been processed, according to Amazon. So fragments of intimate conversations may be captured.

A few days after my wife and I discussed babies, my Kindle showed an advertisement for Seventh Generation diapers. We had not mooched for baby products on Amazon or Google. Maybe we had left digital tracks somewhere else? Even so, it felt creepy. Quizzed, the little black obelisk in the corner shrugged off any connection. “Hmm, I’m afraid I can’t answer that.”

With dozens of daily interactions recorded in the app’s history it grows to quite an archive, giving the dates and times I asked Alexa, for instance, to play John Lennon, or add garlic to the grocery list, or check on the weather in Baja California, where I was planning a vacation. Banal footnotes to life, mostly, but potentially lucrative intelligence for a retail behemoth dubbed the “everything store”.

In the app settings you can delete specific voice interactions, or the whole lot. But doing so, the settings warn, “may degrade your Alexa experience”. It is unclear if deleting audio purges all related data from the company’s servers.

This was on a lengthy list of questions I had for the people who designed the Echo and run its servers. Amazon initially seemed open to granting the interviews, then scaled it down to one interview with a departmental vice-president in October. October came and went and Amazon’s press representative went silent, killing the interview without explanation.

Which, to paraphrase Alexa, was not very nice to do.

People who think about technology for a living have a wide range of views on Alexa. “With Amazon Echo, it was love at first sight,” wrote Re/code’s Joe Brown. “The allure of Alexa is her companionship. She’s like a genie in a sci-fi-looking bottle – one not quite at the peak of her powers, and with a tiny bit of an attitude.”

In an interview Ronald Arkin, a robot ethicist and director of the Mobile Robot Laboratory at the Georgia Institute of Technology, was more phlegmatic. Technology advances bring benefits and drawbacks – you can’t stop the tide but can choose whether to stay out, paddle or plunge in, he said.

“Amazon and Google have all sorts of data about our preferences. You don’t have to use their products. If you do, you are approving, as if you are saying, I’m willing to allow this potential violation of my privacy. No one is forcing this on anyone. It’s not mandated à la 1984.”

It is up to us if artificial intelligence technology makes us smarter or dumber, more industrious or lazy, says Arkin. “It is changing us, the way we operate. The question is, how much control do you want to relinquish?”

The Echo, says Arkin, is a well-engineered advance in voice recognition. “What’s interesting is it’s another step into turning our homes into robots.” The prospect does not alarm him. “You see this in sci-fi: Star Trek, Knight Rider. It’s the natural progression.”

Robots move inventory at an Amazon fulfillment warehouse. Amazon installed more than 15,000 robots across 10 US warehouses, a move that promises to cut operating costs by one-fifth. I’m not concerned about the commercial use of robotic systems and artificial intelligence type applications when used in commerce or manufacturing, but I don’t think they fit into the homes of informed people who love privacy, property rights and freedom.

Ellen Ullman, a writer and computer programmer in San Francisco, sounded much more worried. The more the internet penetrates your home, car or body, the greater the danger, she said. “The boundary between the outside world and the self is penetrated. And the boundary between your home and the outside world is penetrated.”

Ullman thinks people are mad to use email supplied by big corporations – “on the Internet there is no place to hide and everything can be hacked” – and even madder to embrace something like Alexa.:

Such devices exist to supply data to corporate masters: “It’s going to give you services, and whatever services you get will become data. It’s sucked up. It’s a huge new profession, data science. Machine learning. It seems benign. But if you add it all up to what they know about you … they know what you eat.”

Ullman, the author of Close to the Machine: Technophilia and Its Discontents, is no luddite. She writes code. But, she warned, every time we become attached to a device our sense of our lives is changed. “With every advance you have to look over your shoulder and know what you’re giving up – look over your shoulder and look at what falls away.”

Ullman’s warning sounds prescient. Yet I’m not rushing to banish Alexa. She still perches in my living room, perhaps counting down the days until her Guardian media embed ends and she can return to Seattle. She turns my musings and requests into data and uploads them to the cloud, possibly into the maw of Amazon algorithms. But she’s useful. And I am weak. I’m not with her, I think it’s a bad idea.

Some people like to “bow to the god of convenience”. A day will come when I’m alone in the kitchen, cooking with sticky fingers, and I’ll need reminding how many teaspoons are in a tablespoon.

Appliances & Devices

Think you are safe in your own home? These innocent-looking devices may be spying on you, or performing other nefarious actions:

Your Kitchen Appliances

Many recent-generation kitchen appliances come equipped with connectivity that allows for great convenience, but this benefit comes at a price – potential spying and security risks. Information about when you wake up in the morning (as extrapolated from data on your Internet-connected coffee maker) and your shopping habits (as determined by information garnered from your smart fridge) can help robbers target your home. Furthermore, potential vulnerabilities have been reported in smart kitchen devices for quite some time, and less than a month ago a smart refrigerator was found to have been used by hackers in a malicious email attack. You read that correctly – hackers successfully used a refrigerator to send out malicious emails.

Your DVR/Cable-Box/Satellite-TV Receiver

Providers of television programming can easily track what you are watching or recording, and can leverage that information to target advertisements more efficiently. Depending on service agreements, providers could potentially even sell this type of information to others, and, of course, they are likely to furnish this information to the government if so instructed.

Think you are safe in your own home? These innocent-looking devices may be spying on you, or performing other nefarious actions:

Your Television

Televisions may track what you watch. Some LG televisions were found to spy on not only what channels were being watched, but even transmitted back to LG the names of files on USB drives connected to the television. Hackers have also demonstrated that they can hack some models of Samsung TVs and use them as vehicles to capture data from networks to which they are attached, and even watch whatever the cameras built in to the televisions see.

Your Kitchen Appliances

Many recent-generation kitchen appliances come equipped with connectivity that allows for great convenience, but this benefit comes at a price – potential spying and security risks. Information about when you wake up in the morning (as extrapolated from data on your Internet-connected coffee maker) and your shopping habits (as determined by information garnered from your smart fridge) can help robbers target your home. Furthermore, potential vulnerabilities have been reported in smart kitchen devices for quite some time, and less than a month ago a smart refrigerator was found to have been used by hackers in a malicious email attack. You read that correctly – hackers successfully used a refrigerator to send out malicious emails.

Your DVR/Cable-Box/Satellite-TV Receiver

Providers of television programming can easily track what you are watching or recording, and can leverage that information to target advertisements more efficiently. Depending on service agreements, providers could potentially even sell this type of information to others, and, of course, they are likely to furnish this information to the government if so instructed.

Your Modem (and Internet Service Provider)

If it wanted to, or was asked by the government to do so, your ISP could easily compile a list of Internet sites with which you have communicated. Even if the providers themselves declined to spy as such, it may be possible for some of their technical employees to do so. Worse yet, since people often subscribe to Internet service from the same providers as they do television service, a single party may know a lot more about you then you might think.

Your Smartphone

Not only may your cellular provider be tracking information about you – such as with whom you communicate and your location – but it, as well as Google GOOG -0.12% (in the case of Android), Apple AAPL +0.26% (in the case of iPhones), or other providers of software on the device, may be aware of far more detailed actions such as what apps you install and run, when you run them, etc. Some apps sync your contacts list to the providers’ servers by default, and others have been found to ignore privacy settings. Phones may even be capturing pictures or video of you when you do not realize and sending the photos or video to criminals!

Your Webcam or Home Security Cameras

On that note, malware installed on your computer may take control of the machine’s webcam and record you – by taking photos or video – when you think the camera is off. Miss Teen USA was allegedly blackmailed by a hacker who took control of her laptop’s webcam and photographed her naked when she thought the camera was not on. Likewise, malware on computers or hackers operating on those machines could potentially intercept transmissions from security cameras attached to the same network as the devices (some cameras transmit data unencrypted), and copy such videos for their own systems. Such information is invaluable to burglars.

Your Telephone

It is common knowledge that the NSA has been tracking people’s calls. Of course, phone companies also track phone calls as they need call information for their billing systems. So, even if you use an old, analog phone your calls may be tracked. If you are receiving phone service from the same provider as you get your Internet and/or television service, phone records are yet another element of information that a single party knows about you.

Your Lights, Home Entertainment System, and Home Alarm System

Various newer lighting, home entertainment, and home security systems can be controlled via Wi-Fi or even across the Internet. Remote control is a great convenience, but it also raises questions as to whether information is reported to outside parties. Does your alarm provider get notified every time you come and go? Is information about your choice of audio entertainment relayed to manufacturers of the equipment on which it is played or the supplier of the music? Could hackers gather information from smart lighting, entertainment, or security devices – or the networks on which they communicate – to determine patterns of when you are home, when you are likely to have company over, and when your house is empty?

Your Thermostat (Heat and/or Air Conditioning)

Various Internet-connected thermostats are now available. They provide great convenience, but might they also be transmitting information about your preferences to others? Google’s acquisition of Nest has raised interest in this issue – but Nest is not the only provider of such technology. There are even products distributed by utilities that raise concerns. In my area, for example, the utility company offers a discount to people who install a thermostat that allows the utility to remotely cycle air conditioning on and off in case of excessive power demand. Might that thermostat – or future generations of it – also report information to the utility company?

Your Laundry Equipment

Like kitchen appliances, washers and dryers that connect to the Internet may report information that users may not realize is being shared, and that if intercepted, or misused, could help criminals identify when you are home and when you are not.

Your Medical Devices

It is not news that pacemakers, insulin pumps, and other medical devices can be hacked. But even normal functioning devices may spy on you. Various pacemakers relay patient status information over the Internet – this may be valuable in some cases, but also creates risks. Could unauthorized parties obtain information from such data in transmit? What if a criminal sent out phony “pacemaker impersonating” messages stating that a patient is in distress in order to have his physician instruct him to go to the hospital – and leave his home vulnerable?

Your iPod or Other Entertainment Devices

Yes, there are still millions of people using specialized non-phone-equipped electronic devices, but these devices are often Wi-Fi enabled and pose similar to risks to smartphones as discussed above. Of course if you are reading books or magazines, watching videos, or listening to audio supplied by an online provider, your choices and preferences are likely being tracked.

Coming Soon… Your Handgun

Millions of Americans keep guns in their homes, so privacy issues surrounding firearms are an issue regardless of one’s position in the perpetual American debate about gun control. In the near future so-called “smartguns” – firearms that contain computers with various safety capabilities intended to prevent accidents and curtail unauthorized use – are expected to enter the market. But, will the embedded computers also spy on the firearms’ owners? Do the guns contain circuitry that might allow law enforcement to track – or even to disable – the weapons? It is hard to imagine that governments would not be interested in adding such “features” to weapons; the US government is alleged to have installed malware onto thousands of networks and placed spy chips into computers, and known to have lost track of weapons it intended to monitor. Would the government really treat firearms as being less worthy of spied upon than telephones?

Vendors may attempt to address some of the aforementioned concerns, but many of the issues are sure to remain for quite some time. So, if you want to take advantage of the benefits of connectivity and smart devices, keep in mind the privacy risks and act accordingly.

RF Radiation From Power Transmitters In Smart Appliances

We recently bought a new American style refrigerator for our kitchen at home. I make a point of testing with my RF (radio frequency) meter everything electrical I bring into my home. Smart appliances are electrical appliances which have been fitted with a power transmitter. The power transmitter connects to the wireless smart meter installed in your home via a WiFi like network signal. This then connects to the ‘smart’ grid via the ‘home area network.’ (HAN). The data from the appliance is collected, just like from Alexa, and transmitted through the SMART meter network into a database somewhere. What is being done with that data? Well, we’ll get to that soon enough.

You can see that RF (microwave) radiation is being emitted from the refrigerator because I only get a reading when the fridge is plugged in. My old fridge did not give off any such radiation. Why is that? Well of course, it did not have any RF emitter. The new refrigerators are smart appliances, they do emit radio frequencies with the information data and harmful radiation, such as microwave bandwidth.

Smart appliances are electrical appliances which have been fitted with a power transmitter. The power transmitter connects to the wireless smart meter installed in your home via a WiFi like network signal. This then connects to the SMART grid via the ‘home area network.’ (HAN).

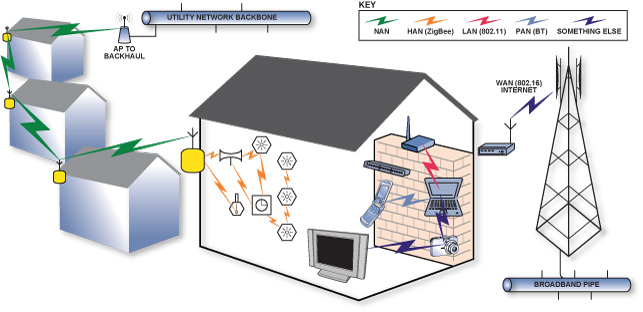

How Does The Smart Meter Network Work?

Smart Meters networks can work in different ways. One way is as shown in this diagram. Inside the home there is a Home Area Network (HAN) and then a cell phone signal type network, Wide Area Network (WAN) sends data back to the utility company.

Where it says “in-home conservation and demand management services” what this actually means is that we are being bathed in more electrosmog (electromagnetic fields) from all the electrical appliances in our homes which are fitted with these wireless power transmitters.

Is Smart Appliance Radiation Dangerous?

Richard Tell an electrical engineer formerly with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in a 2008 report on Smart Grids for Hydro One Networks, Inc./Toronto established that antennas on smart appliances may transmit at a density of .18watts, each at about 4.5 seconds per hour.

Cumulative Effects Of RF Power Transmitters On Smart Appliances

This may sound low but it’s the cumulative effects of the EMFs from these RF power transmitters that are the problem. Imagine 3 or 4 or 5 smart appliances (or more possibly) giving out RF radiation in your home in addition to exposures from your neighbors’ smart appliances. Is this dangerous?

Richard Tell an electrical engineer formerly with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in a 2008 report on Smart Grids for Hydro One Networks, Inc./Toronto established that antennas on smart appliances may transmit at a density of .18watts, each at about 4.5 seconds per hour.

Smart appliances work independently of smart meters. This means that you get zapped with the radiation from smart appliances whether you have a smart meter or not. And if your home is fitted with a smart meter, your exposure is higher in 2 ways:

1. Smart meters are continuously sending HAN information both to the in-house display (if you have one) and to the smart appliances using WiFi, Z-Wave, Zigbee or other wireless communication protocols.

2. There is a separate, higher powered signal being sent to and from the utility company. This signal may be sent every few seconds or every few minutes depending on your provider.

There is a way to protect yourself, many ways actually. I found the solution to my problem by sending the refrigerator back to the retailer. When I now buy any appliances, refrigerator, oven, washing machine, dishwasher etc. I make a point of going in the shop first and asking the sales clerk if I can test the appliance with my RF meter before I buy. I’ve found a local electrical retailer sympathetic to my concerns. When I go to see him, he switches everything off in the shop, WiFi router, cordless phones etc. for a few moments so I can do my testing. This can raise a few eyebrows from passersby, but I’m not concerned with this. RF radiation from smart appliances has no place in my home!

The RF meter I used previously was the Acoustimeter AM-10. The Acoustimeter is really an excellent RF meter and if you’re experiencing symptoms around EMFs it’s what I recommend. You can read my review here.

If you’re not exceedingly sensitive to electric fields, a cheaper alternative is the Cornet ED88T which offers multi-functionality,

Here is an example of how you can disable these; https://youtu.be/SZBo38uNono Go to the Refrigerator Control panel (by water/ice dispenser) and hold the Smart Grid Connect button for 3 seconds. You’ll see it go from the wifi display to a different display which means you just turned wifi off on the fridge. If you hold it again for 3 seconds, you’ll turn it back on. Unfortunately, every time you have a power failure in your house, it will default to turning wifi back on so you’ll need to go turn it off again.

RF Wireless Eavesdropping Devices

The most common type of wireless eavesdropping device, the “BUG”, is a covert listening device placed into an area, hidden from the targeted individual, that transmits audio to a remote location, where that information can be directly monitored and/or recorded.. The basic “bug” is comprised of a small, tiny microphone, electret or condensor type, which is used to change sound waves into electrical signals, then amplified by electronic circuitry which is then modulated and transmitted.

A few examples of what a “bug” looks like:

There are 3 main classifications of “bugs”:

- Active bug – this type of bug is the simplest, as it’s transmitter remains on or active all of the time

- Passive bug – this type of bug can be triggered to turn on whenever it is needed, to save battery life and be more difficult to detect

- Voice activated bug – is only triggered to transmit when sound is received.

- Burst bug – this bug is triggered from any outside signal source, directly from the eavesdropper.

- Wired bug – physically seperated microphone from transmitter, as which the microphone may be installed in one area, and the transmitter into another

Some common different types of operational bugs that are used in RF

- Simple audio modulation and transmission – easily picked up by a simple receiver or scanner

- Digitally encoded transmission – received by a special receiver with decoder.

- Spread Spectrum transmission – otherwise known as frequency hopping, as this type of modulation changes the actual center frequency of transmission many times a second in which a specialized receiver is used to intercept. This makes the overall finding of the bug’s transmitting frequency difficult.

- Single or Double modulated side band – (SSB, DSB) – where the modulation of the signal is found only in the sidebands of the transmission. Can only be received with a special receiver or equipment tuned to the modulation of the carrier.

- FM, NFM, WFM, or AM – common types of modulation such as Frequency Modulation, Narrow-Band Modulation, Wide-Band Modulation or Amplitude Modulation.

Overview of All wireless Bugs

- Small in physical size and can be disguised as almost anything. Devices can also be installed directly into a premises.

- Transduce audible sounds into an electrical impulse, which is then amplified, modulated and transmitted to a remote location for monitoring.

- They emit radio waves of some type.

- Usually lower powered to medium powered RF transmitters.

- They are powered by batteries or leech power from the AC wiring in a residence or DC power in a vehicle.

- Are received by some type of special radio receiver.

- Can be found with an “All Band Receiver” or counter-surveillance receiver

The wireless video transmitter

The newest type of wireless transmitter is now using video. With video, the eavesdropper can now see the occupants and area under surveillance. As video can be transmitted to a remote location, without the knowledge or consent of the individual, a whole new world of eavesdropping now exists.

The basic “video bug” or video transmitter consists of a lens or aperature in which optical infomation is transfered to a series of photo cells, usually in a grid pattern. The CCD or Charge Coupled Device receives light strength and/or colors which is commonly interpreted by a microchip. The signal is then encoded, which in turn is processed into a standard video pattern, which is then modulated and transmitted by means of RF (Radio Frequency).

Even though the video bug or video camera could transfer information wired or wireless, the wireless method is now often preferred, because the surveillancer no longer needs to run wiring or cables to his remote location. This new method of wireless transmission makes covert video transmitters easily placed on a premises or into existing equipment such as appliances and home electronics, making placement easy, portable, cost effective and covert.

A few examples of what the basic “video bug” looks like:

A few examples of what the “video bug” could be placed into, for concealment:

There are 3 main classifications of “video bugs”:

- Active video bug – this type of video bug is the simplest, as it’s transmitter remains on or active all of the time

- Passive video bug – this type of bug can be triggered to turn on whenever it is needed, to save battery life and be more difficult to detect

- Visual activated bug – is only triggered to transmit when the light source changes

- Burst video bug – this bug is triggered from any outside signal source, directly from the eavesdropper or may be triggered at certain time intervals

- Wired video bug – physically seperated camera from transmitter, where the actual CCD lens may be installed in one area, and the transmitter into another

Some common different types of operational video bugs that are used in RF

- Simple video modulation and transmission – easily picked up by a simple television receiver or scanner

- Digitally Encoded transmission – received by a special receiver with decoder.

- Spread Spectrum transmission – otherwise known as frequency hopping, as this type of modulation changes the actual center frequency of transmission many times a second in which a specialized receiver is used to intercept. This makes the overall finding of the bug’s transmitting frequency difficult.

- Single or Double modulated side band – (SSB, DSB) – where the modulation of the signal is found only in the sidebands of the transmission. Can only be received with a special receiver or equipment tuned to the modulation of the carrier.

- FM, NFM, WFM, or AM – common types of modulation such as Frequency Modulation, Narrow-Band Modulation, Wide-Band Modulation or Amplitude Modulation.

Overview of All wireless Video Bugs / Video transmitters

- Can be small in physical size and can be disguised as almost anything. Devices can also be installed directly into a premises.

- Capture physical light which is converted into an electrical impulse, which is then amplified, modulated and transmitted to a remote location for monitoring.

- They emit radio waves of some type.

- Usually lower powered to medium powered RF transmitters.

- They are powered by batteries or leech power from the AC wiring in a residence or DC power in a vehicle.

- Are received by some type of special radio receiver.

- Can be found with an “All Band Receiver” or counter-surveillance receiver

Detection of RF surveillance devices by Radio Wave Emissions

One of the first things an electronic technician learns about is the famous “spurious emissions of radio waves”. In today’s world, we are surrounded with all types of “radio interference”. Many different types of “spurious RF” signals can be sought anywhere in a residence using any type of “Bug Detector” and can be misconstrued as a possible “RF Bug”, leading the sweeping individual into the wrong direction.

Radio interference that can be received from nearby:

- Radio Stations

- Television towers

- Amateur radio operators

- Cell towers

- 60 hertz wiring from a residence

- Fluorescent lighting

- Television sets and VCR’s

- Computers

- Power and Electrical Boxes

- and the list goes on…

Inexpensive “bug detectors” on the market are popping up all over the place. The competition sells these products to unwary consumers claiming to be the best and cheapest. Again, this is FAR from the truth.

- Frequency counters are now being sold as “Bug Detectors”. A frequency counter is designed to find the strongest single frequency of a transmitter. These counters in their nature are slow to respond, and will not find Spread Spectrum (frequency hopping) transmitters. The other factor is that these counters will display all “spurious emissions of RF”, giving results of different backround readings of multiple frequencies. This ever changing display of frequencies only adds more to the confusion.

- “Bug Detectors” that feature the “little light” indication or “led indication” only offer simple detection of radio frequencies in general.

- “Bug Detectors” that feature a metronome noise or Geiger counter type pulsing noise, again only offer simple detection of RF, which can be any radio wave including spurious radio emissions..

- “Bug Detectors” that are so small they’ll fit in your pocket that do not include an antenna! Even some units that have a silent vibrating function. Again, not allowing the user for identification of a real signal or background noise.

Valid Methods of Detection:

Having a specialized counter-surveillance device for detection:

- Finding the location of the transmitter – having a device that displays the proximity or amplitude of the signal. This can tell you how close you are to the transmitter.

- Identify what type of signal is detected

- Spurious Emissions – Finding if the signal received is a backround noise or garbage.

- What type of signal are you receiving – is the signal AM,FM,NFM,WFM,SSB,CW,Video.

- Does the signal have intelligence – does the transmitter have an informative signal that pertains to your situation.

- Demodulation of what type of signal you are receiving – the ability to visually see and hear the type of signal of the main RF carrier

The main idea is having the proper equipment to not only locate the RF signal source, but to positively identify and classify the actual content of the transmission.

With the also added ability to tune out unwanted RF sources of “spurious emissions”, our equipment can be very useful in the hands of an individual. With the proper technical literature that is encompassed in our owners and operators manuals, any individual or technician will be able to use the professional features in our equipment, to provide a professional quality counter-surveillance sweep.

As to solve any problem, taking a logical approach to solve a particular surveillance situation is always the right approach. Now with a new knowledge of how surveillance devices work, where they can be placed and how to identify common types of wireless surveillance devices, the individual can now take affirmative action with the proper equipment.

Remember that not all equipment that is sold in the open marketplace for counter-surveillance detection is suitable, nor has all the features needed to provide a detailed counter-surveillance sweep.

Our test equipment uses the latest technological innovations to help the individual or technician in the aid of locating and positively identifying surveillance equipment.

Remember, this type of equipment is only a tool used to aid a person in the field of counter-surveillance. Only a human being using knowledge, skill, and a methodical approach can find a surveillance device and remove it from operation.

Your SMART Meter Really is Spying on You.

It’s collecting data from your use of appliances, and moreover, it’s actually connected to your appliances and communicating with them to collect large amounts of data so that the power company can hold this data and sell it to third parties. This data is being stored for anyone who wants it, including the police, and it doesn’t mean that because you are not involved in any crime that it should not concern you.

Most of the news on this seems to suggest that we should just accept this loss of privacy as part of having new technology. I’ve written this book because I don’t accept it and neither should you.

(NaturalNews) For years, anyone who suggested that the new electronic, Wi-Fi-capable “smart” electricity meters were devices that could be used to snoop on the unsuspecting public was labeled a crazy conspiracy nut. But, as is often the case, those people weren’t off their rockers; they were prophetic.

Further, this technology is actually being celebrated by people who think that the technology is “cool.” They obviously don’t understand that it’s just another nail in the coffin of the Fourth Amendment.

About a decade ago, when smart meters as a concept were starting out, techies and industry observers were touting them as a way to make more efficient use of the nation’s various electric grids. Then as now, that is a noble construct; the problem is that, in order to do that, smart meters would have to be intrinsically invasive in terms of your privacy. This is no longer a conspiracy but reality

How? Because the meters were envisioned to be power “disaggregators” — that is, they were intended to determine which of your appliances used the most electricity, as well as which devices were used more frequently than others. And of course, that data goes somewhere — the power companies, sure, but who else would want it? Government, of course.

Imagine that, at some point in the future, the government will know what appliances you have in your home, which ones you use the most and how often; that information will lead to a host of new rules and regulations and, most likely, targeted “usage” fees (which is a clever way of saying “taxes”). Want to ramp up that microwave (you shouldn’t even be using one at all, but stick with me here)? Well, microwaves require more power than, say, your electric shaver, and maybe you’ve used enough power this week on your microwave so, if you want to use more, you’ll have to pay a fee for that. Same thing with your conventional oven, for that matter. And so on.

Crazy? Conspiratorial? Ask yourself, then, why it makes any difference for electric companies (and whoever else will have access to the data) to know which appliances and products you are using and how often, when they are currently just billing you for the total amount of power used in a month. Why can’t they just continue to do that?

According to Salim Popatia over at a site called Smart Grid News, the concept is rapidly progressing:

The advent of smart meters, like smart phones, was just the beginning. A phone that allowed you to easily check and respond to email (Blackberry circa 2006) was a ten-fold increase in value as compared to the phones of the past. Today, however, the thought of being able to use a phone only for talking and emailing seems archaic. What about taking and editing pictures, paying for my coffee, measuring my steps or the tremendous amounts of other value that third party apps have brought to the smart phone?

“What gets measured gets managed.”

He goes on to say that, soon, the idea that smart meters will be able to tell power companies how much electricity is being used at any given time will seem “archaic.”

“One of the next areas of value comes from taking smart meter data and ‘disaggregating’ it to tell us exactly how customers are using electricity,” he wrote. “Do external devices already do this? Sure. Just as progress in the smart phone world reduced the need for external devices (cameras, alarm clocks, radios, pedometers, navigation systems, etc) the ability to get accurate, appliance level feedback, without the need to invest in external hardware, is the next step in the world of smart meters.”

Popatia lays it all out: “As we all know, what gets measured gets managed.”